A Glittering Night and Sad Colors

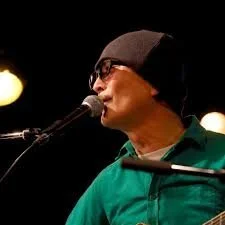

Masaki Ueda (上田正樹) on stage

It was the end of the ninth day of the Folding Bike Tour of Japan – the unstructured “free day” – in Kyoto. To mark her graduation from Mt. Holyoke College as a “non-traditional” student, my 30-year old daughter Nina accompanied me on this, the fourth cycle tour. The tour was going well: we had a compatible group of eight cyclists who were open-minded, curious about Japan, and enthusiastic about tooling around Japanese cities on odd-looking bicycles with small wheels. Still, we all needed a break from each other, hence the free day.

Nina and I sought out streets that were not choked with overseas tourists, a nearly impossible mission in over-visited Kyoto. The Japanese call it kankō osen (観光汚染; “pollution by tourism”). (Note: we were tourists too.) We had limited success in finding quiet places. Weary and frustrated, we sat in a small park in the Gion district and watched as a Western woman decked out in a kitschy rental kimono, a full-blown maiko (舞子; apprentice geisha) getup, complete with a wig to simulate a maiko’s wareshinobu (割れしのぶ) hairstyle, was photographed. The whiteface makeup applied to her face made the woman look like a waxworks figure. It was quite the tableau: cultural appropriation, poor taste, and a desperate drive to gin up a photographic “moment” for Instagram.

Nevertheless, Nina and I were here in Kyoto, a city I have loved since my first visit some 43 years ago. It was our second trip to Japan together and her first as an adult. We were in the middle of an entire month together in Japan. By this point, she’d grown a little tired of being with her father. I never tired of being with her: to me, she is a wonder who fills my heart with joy whenever I look at her. It’s a love that, even after 30 years, I do not fully understand, even as I revel in it.

Nina, who played bass guitar in a touring band for years before returning to college and graduating in December, wanted to hear some live music. She and I spent an hour or so online trying to find a show that evening. She found a club a short bike ride away from where we were staying. Nina found a “live house” (ライブハウス), Club takutaku (磔磔). I have no idea about the origin of this name, but my dictionary, not very helpfully, explains that taku refers to “execution by tying a victim to a post and stabbing with spears.” I sure hope not. A less frightful and more lyrical explanation is found on a website dedicated to student life in the city: “The name comes from a Chinese poem: ‘Like butterflies that flutter and dance, like rivers that flow with a whisper’.” Better, but I remain unconvinced.

Club takutaku (Kyoto)

I checked the website: that night’s show was an artist named Masaki Ueda (上田正樹) and two other performers. Didn’t ring a bell, but we decided to go. It was 5:45 PM and the show started at 6:00. We hopped on our folding bikes and flew through the narrow streets to the venue. (Shameless plug: Brompton folding bikes may be the best way to get around in a city like Kyoto!) We got to the venue in time to snag the very last two seats, which turned out to be a couple of low stools at the back of a crowded room in an old, ramshackle building.

We ordered the mandatory couple of drinks after paying the steep ¥7,000 cover charge (about $49 per ticket). As far as I could tell, we were the only two non-Japanese in the audience of around 200. The crowd was older, 50s and 60s. “Masaki Ueda…where have I heard that name before?”

Ueda came out with Yoshie N (ヨシエ・エヌ; vocals) and Kantarō Uchida (内田勘太郎; bar slide guitar) and launched into the set with a series of covers. They were great! In between numbers, Ueda mentioned playing with the likes of Ray Charles and B.B. King. I was beginning to get the picture: he’s basically a blues man, with the kind of chops that have brought him recognition for decades.

Two or three songs in, Ueda launched into a bluesy version of John Lennon’s “Imagine.” He had me from the get-go: it was the most powerful version of the song I’d ever heard. Nina sat directly in front of me. We were right in the aisle, probably in violation of the Kyoto fire code. Servers kept squeezing past us to deliver drinks to other customers. As the song built to its climax, I was overcome, and Nina heard me openly weeping. She said she cried too. For me there was a deep power in hearing that particular antiwar song sung in Japan, a country that experienced the devastation of total war, in front of an all-Japanese audience, in Ueda’s age-roughened voice. I realized we were in the presence of a legend.

And then he gave an intro he’s given at least a thousand times, something to the effect of “Next, I’m gonna do a little song about Osaka. Maybe you know it…” And everybody knew it. It’s what they came to the show to hear. After the opening bars, I knew it too: It was the song I remembered as “Osaka Bay Blues,” one of the biggest hits of 1983, during my first year in Japan. It remains Masaki Ueda’s biggest hit. The title in Japanese is Kanashii iro ya ne (悲しい色やね), the “ya ne” instantly identifying the lyrics as Kansai-ben, the distinctive dialect of Osaka. The title translates roughly as “a sad color, isn’t it?”

Looking out at the misted lights of the town,

The seats reclined in the car parked on the dock.

We shouldn’t cry – if we cry

We’ll just feel more sad.

[refrain, in English] Hold me tight! – Osaka bay blues

I ask you if you still love me –

Hold me tight!

Has it come to this, that I can’t even tell?

The sea off of Osaka is a sad color,

Because everyone comes here to say goodbye.

The song is a lush, romantic ballad that speaks of “Many rivers flowing through this city/That sweep away all the fragments of love and dreams into the sea.” And like those rivers flowing to the sea, the song brought back a flood of memories: Youth, forbidden love, the sights, smells, and sensations of Japan. In its original incarnation, Ueda was backed by a full string section and a wailing alto sax, very 1980s pop.

In the middle of the set, there was a flood of a very different sort: A pipe in the ceiling sprang a leak, dripping water onto the audience. The venue’s staff members – all of whom seemed to be decades younger than the audience – sprang into action with buckets and towels. Someone figured out how to shut off the water. Ueda, without missing a beat, said “Not to worry about the leak, folks: I’ve brought a change of shirt!” Club taktaku is 50 years old, and the building itself, a converted saké warehouse, is over 150 years old (hence the leaking pipe). A lot of music and history have flowed within those walls; there’s bound to be a leak or two.

Nina sat directly in front of me and I could not see her face. She does not understand Japanese, but I know she was taking in a scene which, for all its strangeness, also had a certain familiarity. The mess of memorabilia decorating the walls, Yoshie N singing in a rich, powerful voice reminiscent of Aretha Franklin, Etta James, and other great Black singers. Kantarō Uchida playing crackling, blues-inflected bar slide guitar. At the appropriate time, Ueda invited the audience to clap along to the rhythm of the music, which they did, dutifully. It was a great show.

At the end of the show, after a single encore, the musicians lined up near the club’s exit for the obligatory photo op (I regret not snapping a picture). The crowd quietly made its way through the single open door. Nina and I unlocked our bikes and flew back through the cool mid-April night to our lodgings.

Masaki Ueda’s set brought up powerful emotions in me. Those emotions are present even now, weeks after that night. It’s not easy for me to trace their source, but my feelings certainly have something to do with the inexorable flow of time. I first heard Masaki Ueda’s music over 40 years ago when I was 25 years old, in Japan for the first time. I was hopelessly romantic and adrift. Over 20 years later, my daughter was 10 years old when I first brought her to Japan. She looked adorable and bookish in the glasses we thought she needed to wear (and which soon proved unnecessary), and now, nearly 20 years later, we are together in Japan again, and Nina is 30 years old. (This accounting of years and the passage of time is something I often find myself doing deep in the night, when I cannot find sleep.) Someone, somewhere, must have said: “To live and love is to learn to let go.” Must have been the Buddha.

It is hard to let go.

Perhaps inevitably, I’m reminded of another lyric, a song from 1980, the Alan Parsons Project’s “Time”:

Time, flowing like a river

Time, beckoning me

Who knows when we shall meet again

If ever.

But time

Keeps flowing like a river

To the sea…

Thank you, Masaki Ueda, Yoshie N, and Kantarō Uchida for a memorable show. And thank you, Nina, for coming with me on this journey through time to Japan.

Nina in Japan