A Letter from Masako

The letter is neatly folded in its envelope where I had taped it into the pages of my journal 40 years ago. But the tape had long since dried out and the letter sits loosely between the pages.

Let the young woman speak for herself.

July 15, 1983

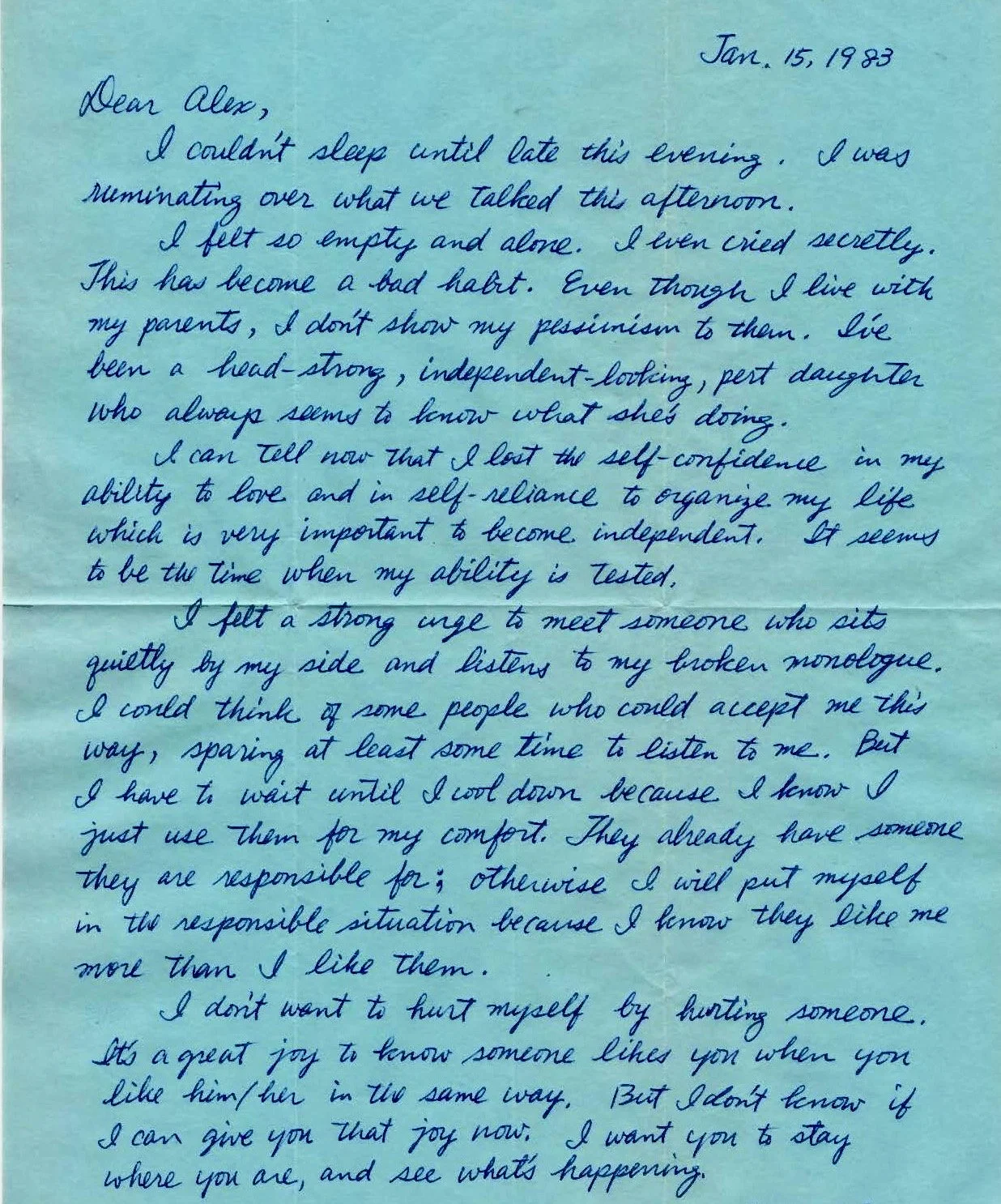

Dear Alex,

I couldn’t sleep until late this evening. I was ruminating over what we talked this afternoon.

I felt empty and alone. I even cried secretly. This has become a bad habit. Even though I live with my parents, I don’t show my pessimism to them. I’ve been a head-strong, independent-looking, pert daughter who always seems to know what she’s doing.

I can tell you now that I lost my self-confidence in my ability to love and in self-reliance to organize my life, which is very important to become independent. It seems to be the time when my ability is tested.

I felt a strong urge to meet someone who sits quietly by my side and listens to my broken monologue. I could think of some people who could accept me this way, sparing at least some time to listen to me. But I have to wait until I cool down because I know I just use them for my comfort. They already have someone they are responsible for; otherwise I will put myself in the responsible situation because I know they like me more than I like them.

I don’t want to hurt myself by hurting someone. It’s a great joy to know someone likes you when you like him/her in the same way. But I don’t know if I can give you that joy now. I want you to stay where you are and see what’s happening.

Masako

I was 24 at the time. I had started my journal, the blank book a gift from my girlfriend in New York, in the spring of 1982 as I sat on a cheap and horrendous flight that, after around 36 hours of hard traveling, eventually took me to Japan. I’ve kept a journal ever since.

It’s embarrassing, even painful, to read those entries from my first time in Japan. In the journal, I’m falling in pathetic, indiscriminate love with nearly every woman who crosses my path. I should be kinder to my past self: it had taken him a long time to figure how to have a girlfriend at all.

Masako was in her mid-20s. She had spent time overseas as an exchange student and, as attested by her letter, both her spoken and written English were excellent. She was managing the local branch of a chain of English conversation schools named “Amvic” (apparently derived from “American victory”; I do not know why a business started and run by Japanese people had such a jingoistic name). English conversation “schools,” usually little more than storefronts with a couple of rudimentary classrooms, were all the rage in Japan at the time. These Eikaiwa kyōshitsu (英会話教室) usually employed bilingual Japanese teachers, but the real draw was the chance to learn English from a genuine native speaker, preferably a white American. Although in Japan, English was taught throughout the entire six years of middle school and high school, nearly all English teachers were Japanese, and very few of them were competent or expected to teach English as a language actually spoken by anyone. One of the instructors at this particular Amvic branch was a Japanese-American woman from California who had graduated from Stanford but, being at least a third generation American, spoke little Japanese. Life in Japan was hard for her because she did not fit the mold of what Japanese people believed an English-speaking person should look like.

Like many Western men, I was fascinated by Japanese women, but understood little about Japan, its language or culture. I understood nothing about the hazards of projection, of imposing my own notions on others without seeing them for who they actually are. There was nothing particularly remarkable about Masako. She was obviously deeply sensitive and intelligent, but she had another aspect that I found irresistible: she was sad and lonely. It’s clear in my journal that I thought I was ready to sweep her off her feet and carry her back to the U.S. with me. Luckily for both of us, Massako was far more sensible than I. She saw that I was desperate and had no meaningful understanding of love, knew nothing about marriage, and had little understanding of the world she came from.

With 40 years of hindsight, what most troubles me about this episode is how quickly I moved on. Before I’d even read Masako’s letter, I was done with her:

She said she distrusted feelings and I pointed out that if she refuses to trust her own feelings, bottles them up & fails even to acknowledge their existence, she’d best resign herself to a lonely lifetime here & now. Said all I had to say, kissed her & left. She just called to tell me she wrote some kind of letter to me. I’ll read it tomorrow. Pretty sure it’s a polite refusal.

…as indeed it was.

But her letter reveals that Masako did acknowledge her feelings. I see now that she was a young woman who, confronted by a complex set of feelings and circumstances, had the insight and wisdom to hold back and think things through for herself. I see now that she was emotionally mature in ways that the young man to whom she addressed that letter was not.

I can only begin to imagine how difficult it was for a single Japanese woman in the early 1980s. Career options were limited. Marriage and motherhood were expected. A woman who spent a lot of time with gaijin (外人; foreigners) was marked as different and, in a society like Japan that privileges conformity, different is not better. Over the intervening four decades, things have changed in Japan. I recently met a woman who, after teaching English in Japan and abroad for a few years decided to return to university to study medicine. She failed the entrance exam twice, but passed on the third try. She became a brain surgeon, met and married an anesthesiologist, had two children at around age 40, and now practices rehabilitation medicine. Such a career path for a woman who chose to remain in Japan would have been virtually unheard of in 1980s Japan. Countless Japanese women have opted to leave Japan because there simply were more available choices in foreign countries.

I left Japan in the spring of 1983 and soon lost contact with Masako and most of the people I had gotten to know in the nine months that I lived in Kurashiki. I returned to the U.S., earned a master’s degree, and married an American woman from New Jersey. In September 1985, she and I went to Japan, this time for three and a half years.