Go with the Fold in Tokyo!

Touring Japan by folding bicycle

Setting out in Tokyo (left to right): Nina, Duane; Monica, Eliete, Larry, Scott, Jeannie, Howard, Nicola, me)

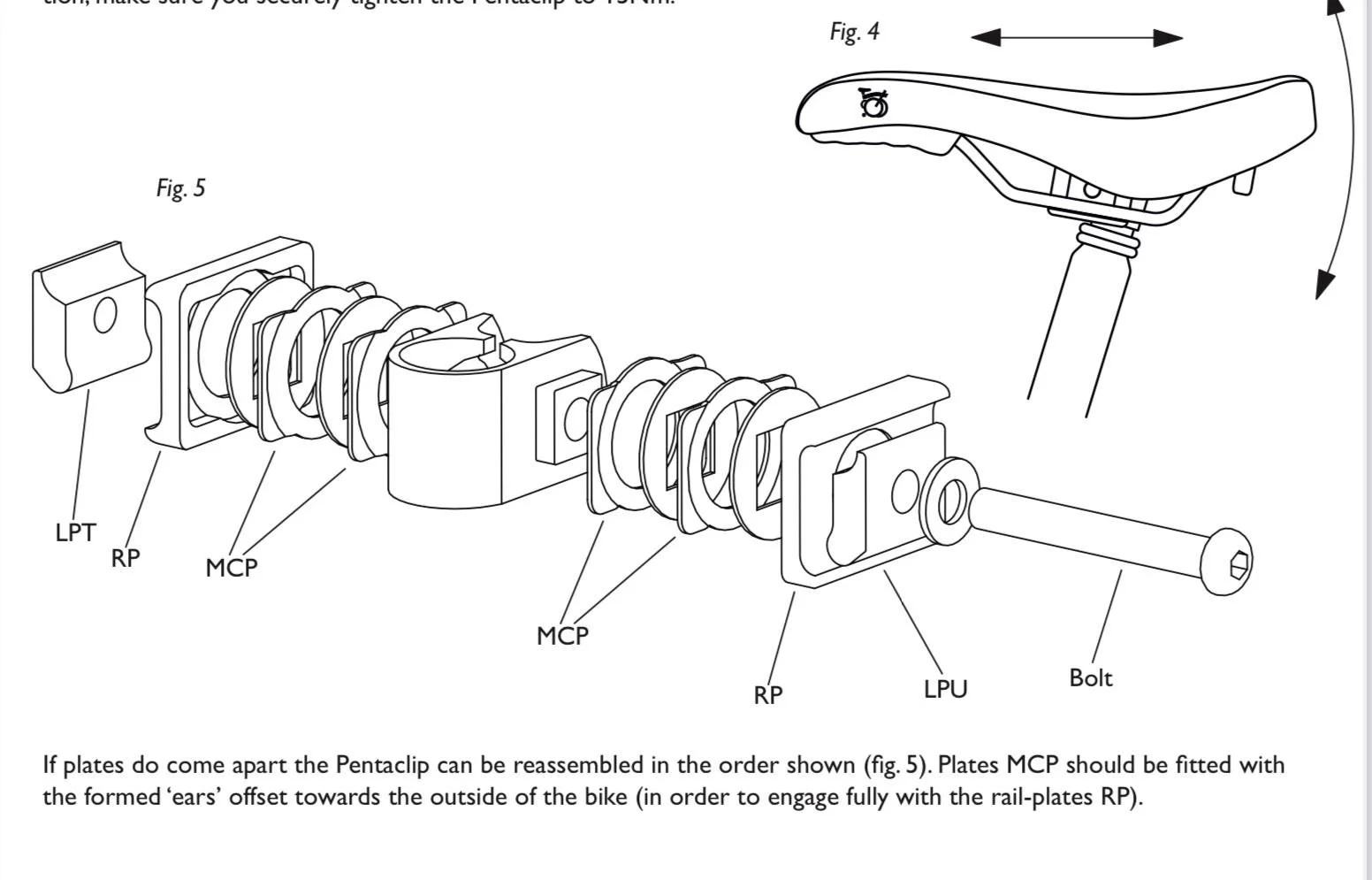

Howard and Jeannie were new to Brompton folding bikes. They bought their C-Line 6-speed bikes used in New York City, where they live. Unfortunately, when Howard put his bike into its dedicated travel case for the New York to Tokyo flight, he went just a little too far. The Brompton is renowned for its ability to fold and unfold in seconds, but one must never, I repeat never, remove the bolt that tightens the seat clamp to the seat post. This is exactly what Howard did, and in doing so, the notorious “pentaclip” disassembled itself into over two dozen pieces. Not knowing how these weird little pieces go together, Howard put them in Ziplock bag which he duly handed to me in front of our hotel near Tokyo Station. This was my first mechanical of the April 2025 Folding Bike Tour of Japan.

The notorious Brompton pentaclip

I love cycling, I love cities, and I love Japan. In 2016, I came up with a way to combine folding bicycles with these other two loves. Ingenious human-powered contraptions, folding bicycles fit into regular-sized suitcases and can be taken as checked luggage. Upon arrival, the bike can be quickly unfolded and made ready to ride. A bike is an excellent way to see Japanese cities like Tokyo and Kyoto. And with folding bikes there’s no need to ride between these cities because Japan has one of the world’s greatest passenger rail networks. Passengers can take bicycles onto most trains, with one important proviso: the bike must be fully covered from the moment it’s taken through the ticket gate at the departure station until it is carried through the ticket gate at the arrival station. A cover is needed to protect other passengers and the trains themselves from the greasy dirt that typically adheres to bikes.

I design and lead two-week tours that have included visits to Tokyo, Kamakura, Kyoto, a ride across the Inland Sea on the Shimanami Kaidō, a ride along Lake Biwa (Japan’s largest lake), a visit to the city of Kanazawa near the Sea of Japan, ending with two-night homestays in rural Shiga Prefecture. The first tour was in 2016, and I’ve led three since then. I’d hoped to run the tours annually or semiannually, but that plan was overturned by the pandemic. After the pandemic, I resumed tours in 2024 and 2025.

All members of the April 2025 group were retired, with ages ranging from mid-60s to mid-70s. On this tour, my 30-year-old daughter Nina joined me, riding a Brompton borrowed from a 2024 tour participant. Nina had just graduated from Mt. Holyoke College’s program from non-traditional students and was about to embark on a career in financial planning. Her participation in the tour was my way of congratulating her on her achievement, but self-interest was in play as well: Her job was to ride “sweep” (last rider in the peloton) to make sure no one was left behind, especially this was a larger group with eight paying passengers. It also happens that my daughter is innately skilled in human relations, which is useful in a group where people are apt to wander off in different directions.

People had a variety of careers: Scott was a tall, lanky Air Force nurse who had started his career as a military helicopter pilot from Hawaii; Duane, a dentist from Seattle; Nicola, was also a nurse as well as a dancer; Monica worked for the State Department in a wide range of overseas postings; Eliete, is a colorful Brazilian who had worked as a counselor; Larry was a management consultant; Jeannie was a lawyer for the City of New York; and Howard had worked on Wall Street in IT. Some people were more comfortable on their bikes than others. For example, Larry, who was the oldest rider, is unusually fit. He would often rise at dawn and go out on a 10–20-mile solo ride just to limber up before riding with the group for the rest of the day. Regardless of people’s level of fitness, I set mileages on the lower side during the first week of the tour, working up to a couple of longer rides toward the end. No one got left behind, and no one complained about the amount of riding. (On past tours, however, there were a couple of riders who were disappointed that we were not hammering out more miles each day.)

Racking up high mileage counts is not my goal. The tour is designed to put folding bikes to their best use to extend an individual’s range without recourse to motive power. Conventional tours use tour buses, taxis, public transportation, and walking or some mix of these to get around. Walking is a great way to see a city or even a rural village, but it’s slow-paced and limited. On a walking tour, 7–8 miles per day is about the limit. More than that and all but the most fit walkers wear out and sightseeing becomes simply exhausting. 10–15 miles a day on a bike, however, is easy.

In 2025, we spent a couple of days in cycling around Tokyo. On the first day, a new friend of mine, Aisaku Oruto, whom I met through the Tokyo Brompton Club’s Facebook page, rolled up to our hotel at 9:30. After introductions, we set on a route that Oruto-san had planned for us. Although he is an architect by profession, Oruto-san is a novelist by avocation who has a deep love for Japanese history and the culture of premodern Tokyo. He took us to sites around the Sumida and Onagi rivers (隅田川,小名木川), places made famous in the woodblock prints by Hiroshige Utagawa (広重歌川;1797-1858). We stopped on a bridge over the Onagi River where he showed us a reproduction of a Hiroshige print. In the image, the river has that deep blue for which the ukiyo-e artist is celebrated. Curiously, the river in the print is depicted with a long, lazy bend in it as it vanishes into the horizon. Oruto-san then drew our attention to the river today. He explained that the river, which is actually a man-made canal, is and was 200 years ago straight as an arrow. Hiroshige introduced the curve to create visual interest.

From Hiroshige Utagawa’s One Hundred Famous Views of Edo (名所江戸百景) (Wikipedia Commons)

Aerial view of the Onagi River (Wikipedia Commons)

On our second day in Tokyo, my good friend and language exchange partner, Sumi Ohashi (大橋すみ), met up with us and led us over to Tsukishima (月島) near the mouth of the Sumida River. Sumi has taken my groups to Tsukishima before. The name translates as “moon island” because of its original crescent moon shape. Starting in the 17th century, fishermen were brought over to Edo (present-day Tokyo’s forerunner), by the feudal government. They were commanded to start landfill operations to expand the land area of the island. This work took several centuries and was finished in the 1890s. Sumi likes to go to Tsukishima for a lunch of the local specialty, monja-yaki (もんじゃ焼き). Although Japanese cuisine is noted for beauty of presentation, this clearly does not apply to monja-yaki wheich in its pre-cooked state looks gross. Sumi says ゲロみたい (gero mitai) – “looks like puke”. Consisting of a wheat flour batter laden with chopped cabbage and a variety of meats, it is cooked at the table on a griddle and seasoned with soy-based sauces, mayonnaise, and smoked fish flakes. A distinctly proletarian dish, it tastes a lot better than it sounds or looks. I’d say it’s an acquired taste.

Monja-yaki

Monja-yaki is a part of Tsukishima and its working-class roots. The district is unique in that it escaped destruction in the two great calamities that laid waste to Tokyo twice in the 20th century: The Great Kantō Earthquake and Fire of 1923 and the massive firebombing in March 1945 near the end of World War II. Today, despite the high-rise apartment blocks at its edges, Tsukishima retains much of its prewar character in the narrow roji (路地) or alleyways, most of which are barely wide enough for two people to pass side by side. The island was also once home in the late 19th century to Tokyo’s nascent heavy industry in the form of the factories and graving docks of shipbuilder Ishikawajima-Harima Industries (IHI).

It turns out that cycling in Tokyo, despite its population of over 14 million, is a lot of fun. And cycling through this megacity is much safer than you might think. I’ve given a lot of thought to why this is so. It’s probably because there are already so many bikes on the streets that drivers expect to coexist with lots of cyclists and pedestrians. This is especially true on the side streets, of which there must be tens of thousands in Tokyo. The streets are narrow, often crowded, and consequently vehicular speeds are slow. A cyclist or pedestrian is far less likely to be injured or killed when vehicles cannot travel much faster than 15-20 miles per hour.

Like most cultures, Japan embodies many contradictions. The Japanese are known for their adherence to rules. For example, crosswalks. It may be the middle of the night. There is no traffic. The “walk” sign controlling the intersection of a small side street with an avenue is red. In most other cities, pedestrians would look both ways and charge through. Not so most Japanese: they stop and wait for the green before they cross. Sometimes I think I can read people’s minds as they think “waiting for no cars to pass is kind of silly, but I don’t want to be a rule-breaker…” For all that, however, when it comes to bicycles, there’s a kind of anarchy. Tokyo has surprisingly little bicycle infrastructure other than extensive bike parking facilities. There are very few separated bike lanes. Bike lanes are typically “sharrows,” which are little more than lines and bicycle icons painted on the pavement.

What’s a cyclist to do? Well, in Tokyo as in most of Japan, cyclists ride wherever they can, whether in the street or on sidewalks, nimbly dodging pedestrians and illegally parked delivery trucks and taxis. On the tour, Jeannie, a cyclist hardened by riding the mean streets of New York City, was appalled when I led the group down the wrong way of a one-way street. “This is really freaking me out!” she called out. I pointed to a sign in Japanese which indeed said “do not enter…except for bicycles”! Bikes can go any direction they want.

“Do not enter…except for bicycles”

Leading these cycle tours can be a challenge. I’ve had some participants who were hard to please, including one who clearly went to Japan mainly because she was running low on countries to visit. She did not seem especially interested in what I had to show her. Yet even she managed to find her tribe: In Kamakura, she wound up in a ramshackle little bar on the coast road which was populated by characters straight out of the world of manga (comics) who, like her, enjoyed nothing more than drinking, singing, carousing, and being ridiculous. I’m glad she had a good time.

Most people, however, have better reasons to visit Japan. There was Sam, a retired physician, whose decades-long involvement with Buddhism helped him to savor every temple we visited. A music shop in Kanazawa opened its doors for us so that Richard, an ethnomusicologist, could try out a three-stringed shamisen (sort of an East Asian banjo). Ed, my most senior member at 86, charged up the steep road to our lodgings with the rest of the group at night, utterly astounding our host when I recounted the adventure to her the next morning. Barbara savored every part of the tour, photographing and documenting everything in detail. Monica would fly down every hill with wild abandon on her titanium Brompton. During the homestay portion of the tour, she walked into a sleepy country hair salon and somehow explained with gestures and Google Translate what kind of haircut she wanted. Duane, a veteran Brompton rider (he owns several of these bikes), braved a painful knee to join the tour. As our unofficial Brompton pit crew, he kept everyone else on the road and enjoyed himself thoroughly in Japan. He has proved to be a most loyal supporter and promoter of my tours.

Why do I lead these tours? Beyond the prosaic need to diversify my sources of income, I really enjoy sharing Japan with people who are ready to engage with the country and its culture. To me, it’s a privilege to be the interpreter – in every sense of the word – standing between a local person and a visitor from abroad. For the most part, I’ve felt proud to be the one who brings these visitors to Japan, people who are engaged, curious, and respectful. I’m also glad that my groups’ “carbon footprint” in Japan is relatively small: We use public transit between cities and once at our destination, we ride bicycles, eschewing large tour buses or taxis.

(Shameless self-promotion alert): I’m planning to lead another folding bike tour in April 2026, and I’ve got up to four spaces available. If you’re interested in a two-week train and bicycle odyssey through Japan, let me know!

(PS: Even if you do not own a folding bike, there are ways around this. Talk to me!)

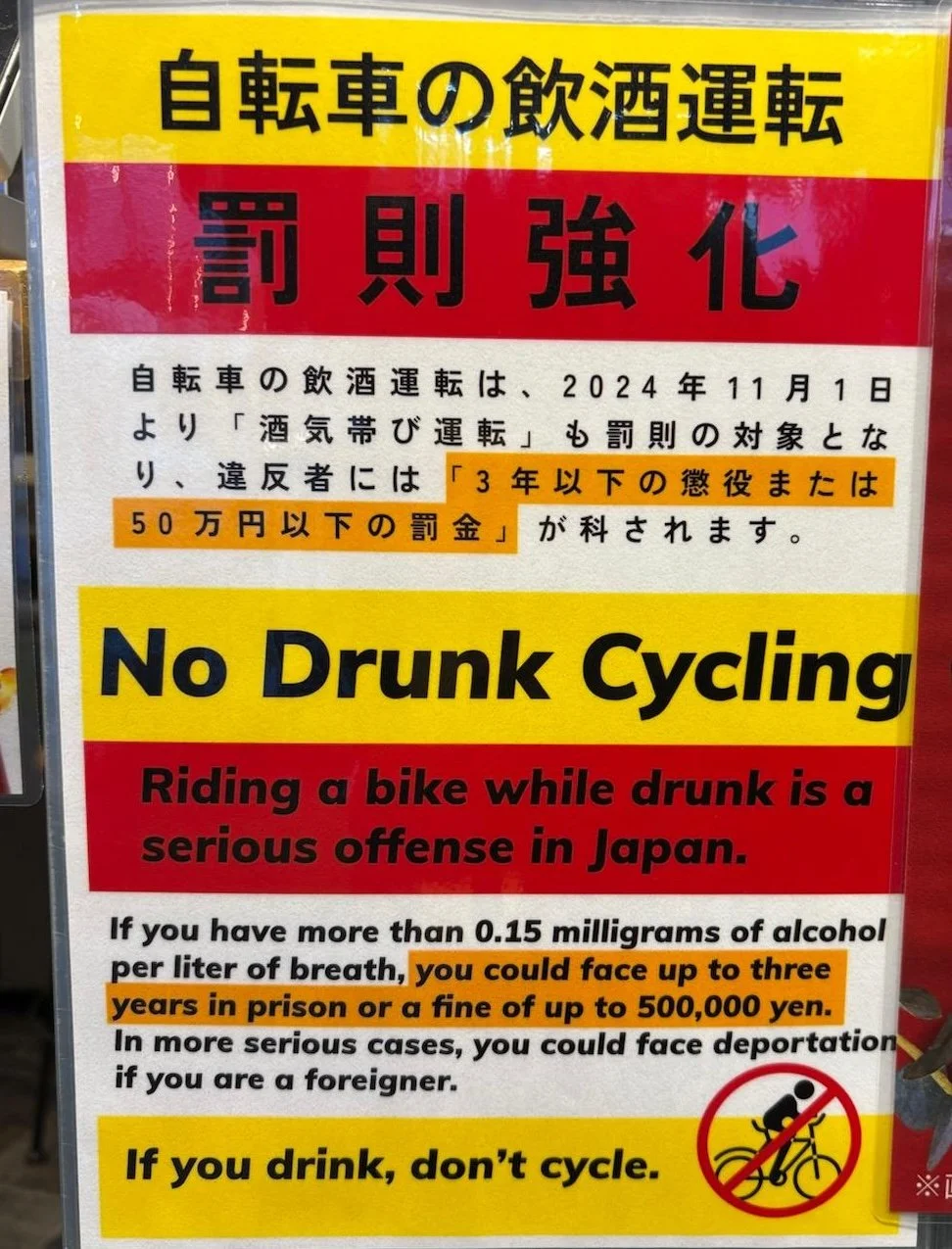

The sign says it all.