The Healing Power of Light

The Kaleidoscope Museum of Kyoto

“Follow me. There’s a bike parking lot around the corner.” With that, I heard the crash as Felicia fell over, her rented e-bike landing on top of her. I leapt off my own bike to go to her, but I could not get the damn bike to stay upright on its kickstand (I needed to shift the lever on the kickstand to make it work properly), so I just dropped it to the ground. Precious moments passed, and then I ran over to her.

Our daughter Emma was already helping her mother up from the side of the street. She’d fallen on one of those ubiquitous low curbs found everywhere in Japan; the country is one huge tripping hazard. Felicia did not seem badly hurt: a few minor scrapes on her leg, but she had twisted her ankle, which later swelled up painfully, and she’d jolted her body, which does not take kindly to that kind of violent movement. She simply was not used to riding an e-bike, and the thing began to take off before she was fully seated on the saddle.

We went around the corner to Oike-dori and found the bike parking lot. (There are so many bicycles in Japanese city that one typically must find an official parking lot. This one cost ¥200 per bike, or about $1.25 at the current rate of exchange.) Emma and I tended to Felicia’s injuries: I bought some ice at a convenience store, and Emma had some sanitary wipes to clean the abrasion on her knee. We comforted her as best we could.

After some time, we walked over to our destination, the Kaleidoscope Museum of Kyoto (京都万華鏡ミュージウムウ) on Ayanokōji Street. I had chanced upon this small museum some years previously when I was in Kyoto to meet met up with Karen, an old friend from Australia who had happened to be in Japan at the same time I was. Karen is an artist. She and I enjoyed the museum, which I took to be just another of the sort of whimsical collections of objects so common in Japan. Japanese people can become deeply, evenly obsessively, devoted to the oddest things. I knew that Felicia and Emma would be entranced by the images created by the bits of colored glass in the little tubes arranged around the single exhibition gallery in the museum.

On this visit, however, I wondered how the museum had come into existence. I asked the small elderly woman who seemed to be a volunteer docent but she did not know the history of the museum. My question set off a flurry of activity, probably because I asked in Japanese and it seemed as if I might actually understand the answer. The docent alerted the woman working in the kaleidoscope-making workshop/café space adjacent to the gallery. She in turn pointed to a long article in English about the invention of the kaleidoscope (by Sir David Brewster of Scotland, ca. 1817). I said “No, how did this particular museum come about here in Kyoto?” More quiet commotion. Soon, the director of the museum, Kazuko Itō came out into the gallery and directed us to a table in the workshop/café.

Itō-san explained that the museum is designed not just to display kaleidoscopic images in the 50 or so kaleidoscopes on display. She said that, while kaleidoscopes had been invented 200 years ago, they had enjoyed a renaissance in the 1980s thanks to the efforts of an American woman, Hazel Cozette Oliver, better known as Cozy Baker. The museum director said that Baker’s son, Randall, had died young (struck at the age of 23 by a drunk driver), and that she found solace in kaleidoscopes. Baker wrote a book about this tragedy and how she came through it. The book was published in 1982 as Love beyond Life: Six Enlightening Ways to Triumph over Tragedy. From the website of the Brewster Kaleidoscope Society:

During her book tour in 1982, she stopped in a small gift shop in Nashville, Tennessee and purchased a kaleidoscope by Doug Johnson. During the entire flight home to Maryland, Cozy was mesmerized by the images of this wonderful new acquisition. 1)

Itō-san said that Japan is second only to the U.S. in the number of active kaleidoscope makers and collectors, with many Japanese members of the Brewster Kaleidoscope Society.

Calmly and quietly, Itō-san described how a kaleidoscope has the power to heal troubled souls. For example, she said, the museum has been involved in distributing kaleidoscopes to children who have survived natural disasters (such as the 2011 Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami that took some 20,000 lives). “When you peer into a kaleidoscope, you have to close one eye to see the image,” she explained. “That way you can close out the world and just see the beautiful colors and patterns formed in the device. You don’t have to think; you just feel. This is why the kaleidoscope has a healing power.” So it’s no coincidence that the museum is adjacent to the Kyoto City Educational Consultation Center and Children’s Counseling Center.

For the past several decades, Japan has experienced an alarming rise in the number of children who simply refuse to go to school. Bullying is a big problem in Japanese schools and many children become resistant to leaving home and going to school. They become alienated and withdrawn shut-ins (hiki-komori, 引きこもり). It is a persistent problem that has complex roots in contemporary Japanese society and the profound changes in Japanese family structure. The pandemic has no doubt exacerbated the problem. The Kaleidoscope Museum of Kyoto works with the Children’s Counseling Center, using kaleidoscopes to help sooth traumatized children. Again and again, Itō-san insisted that kaleidoscopes “have the power to heal.”

I interpreted into English what the museum director was saying so that Felicia and Emma could understand. As I did so, I found myself deeply moved. Simple little cylindrical, square, or prism-shaped tubes containing colored glass, mirrors, a lens at one end, and a viewing aperture at the other. I had visited the little museum years before and had looked through the kaleidoscopes arrayed around the room, but I did not understand their power.

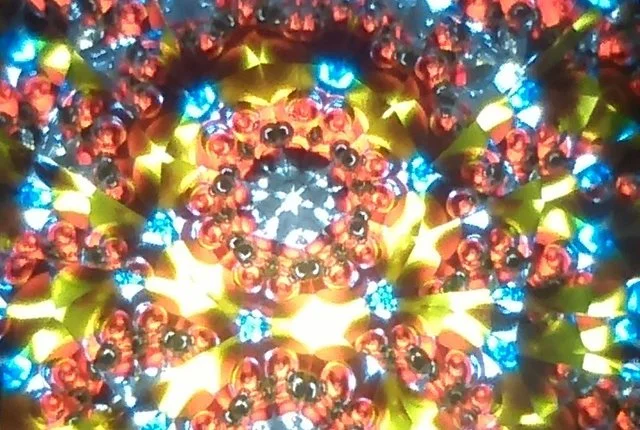

After our meeting with Itō-san, we were invited back into the exhibition space. Once every hour or so, the staff darkens the room and turns on an array of 10 small projectors hanging from the ceiling, transforming the four walls of the gallery into a giant kaleidoscope. Viewers are immersed and transported into a world of colored shapes and light which, perhaps because of the slowly moving symmetries and the absence of narrative, offers comfort and solace.

We bowed and thanked Director Itō and her staff as we left the museum.

When I was a child, a kaleidoscope was an inexpensive toy, maybe a museum gift shop souvenir, that would provide a few minutes of pleasure. The kaleidoscope might ultimately fall to the bottom of the toy box, neglected and forgotten. After our visit to the Kaleidoscope Museum of Kyoto, I will never see these tubes of colored glass, mirrors, and lenses in the same light.

(Kyoto, April 29, 2024)